Dominican Republic

A documentary photo project for Global Links

1999

These images originated from a documentary photography project in 1999. The project was the brainchild of my professor and advisor at Ithaca College, Janice Levy, and two professional photographers Lynn Johnson and Annie O'Neil. Myself and four other former and current students traveled to the Dominican Republic with Janice, Lynn and Annie to photograph the international relief efforts of Global Links, a non-profit organization based in Pittsburgh, PA, which collects surplus medical supplies from US hospitals and distributes them to hospital and clinics in developing countries.

Having just graduated from college, I saw this project as an opportunity to intensely explore documentary photography in the real world. During this experience I met a part of myself and a part of the world which I had never before seen, both of which opened my eyes to a broader perspective on the world and the people who inhabit it.

The text that follows are a combination of excerpts from my journal and reflections that I captured at the end of the project.

Waste Not, Want Not

This project began in Pittsburgh, PA in the early Spring of 1999. To gain a fuller perspective of the lifecycle of the medical supplies that make their way from the US to developing countries, we began by photographing in an operating room in a Pittsburgh hospital. The operating theater highlighted for me not only the sophistication of equipment and techniques employed by the doctors and nurses, but also the sheer volume of waste that is generated from a single procedure. Tools were opened from their sterile packages, and then regardless of whether or not they were used, they are thrown away at the end of the operation. Global Links rescues these tools from the waste stream, sterilizes and sorts them, and then repackages them up for delivery to hospitals and clinics in other countries where they are desperately needed.

From the hospital to the warehouse

Voyerism

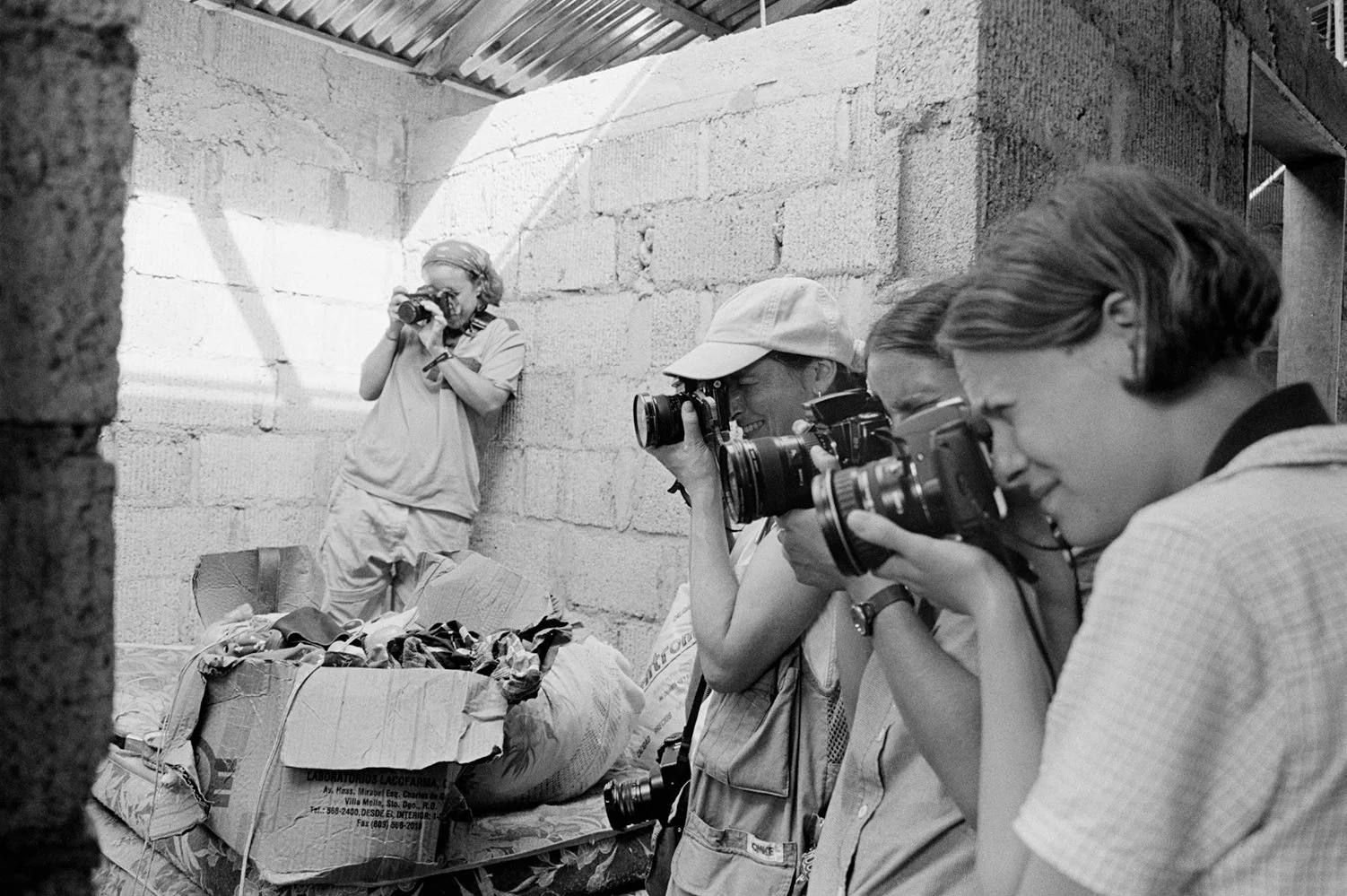

May 9, 1999 - We started the day walking around the city of Santo Domingo. Annie thought it was only a 20 minute walk to the Old City, but it took us almost 2-1/2 hours. We walked around the coastal street, Avienda George Washington. This is where there are a lot of hotels, especially as you get closer to the Old City. At one point we walked up to a group of men who were making nets, and Annie started photographing them. My first reaction was to photography something - anything - else. I felt that photographing them would be objectifying them. My Spanish was limited, and therefore my ability to talk with them to get to know something about them was limited. Eventually I started photographing Lynn and Annie shooting them...

This also became one of many themes I returned to throughout the project. As we walked, I felt more and more the disparity of wealth, as these giant glamorous hotels loom in the background and five year-old kids hustle the American tourists to shine their shoes. When the shoeshine kids approached Annie, I didn't feel right photographing them. For me it would perpetuate what I perceived to be their exploitation, so instead I shot the other photographers shooting them, and the vulture-like hovering that photographers do over their subjects.

Bayaguana Medical Clinic

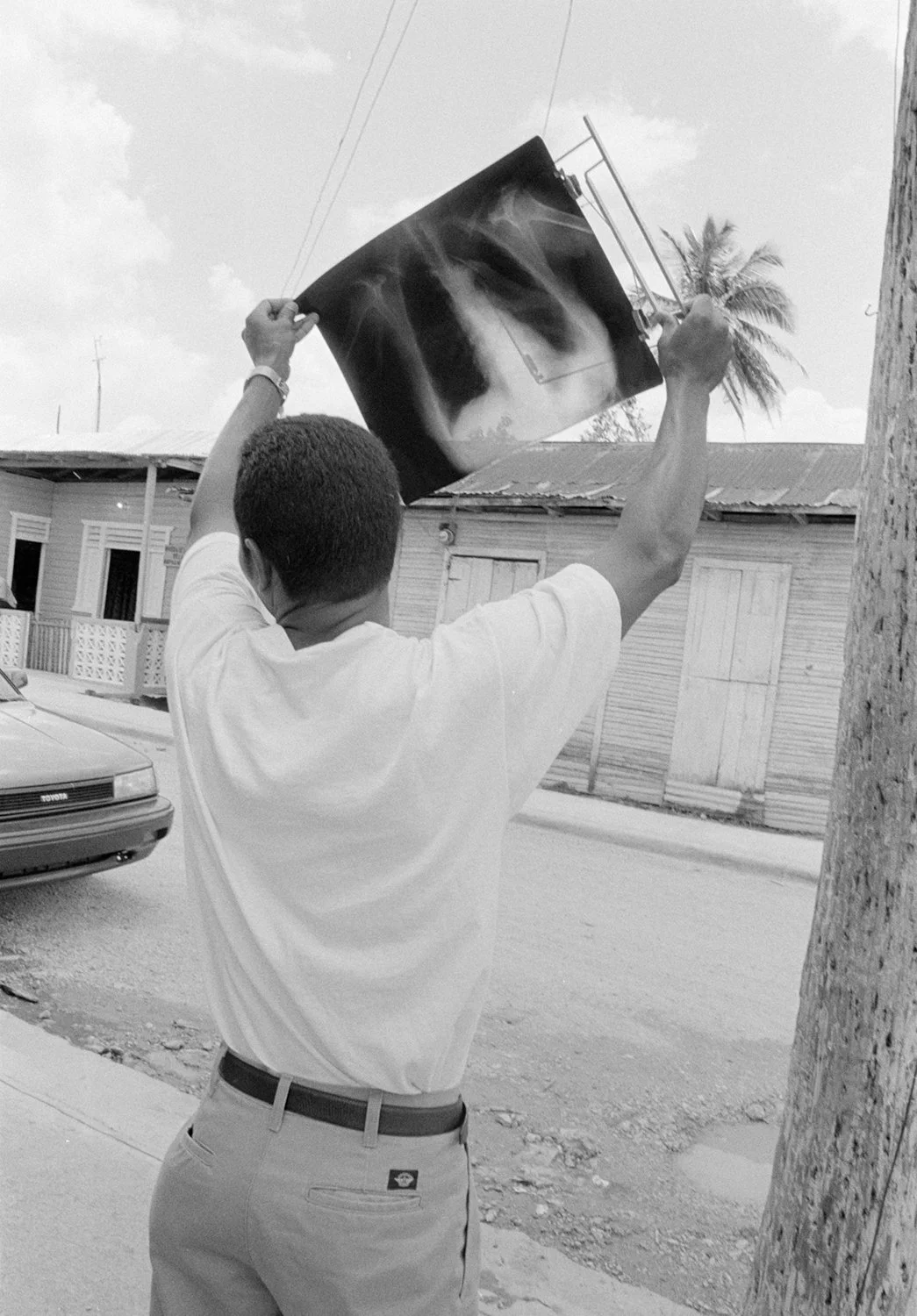

On the way to lunch, Janice noticed a man coming out of a clinic holding a wet X-Ray up to the sun. He hung it on a telephone pole to dry. She got so excited about the potential photograph she wanted to make of him, and it just sucked the enthusiasm right out of me. I might have felt differently about the situation if I was alone, but she kept referring to it as a "photo opp", which bothered me because I felt it objectified the moments that are part of a person's life so that a photographer can take it. It optimizes what I am uncomfortable with in a lot of documentary photography.

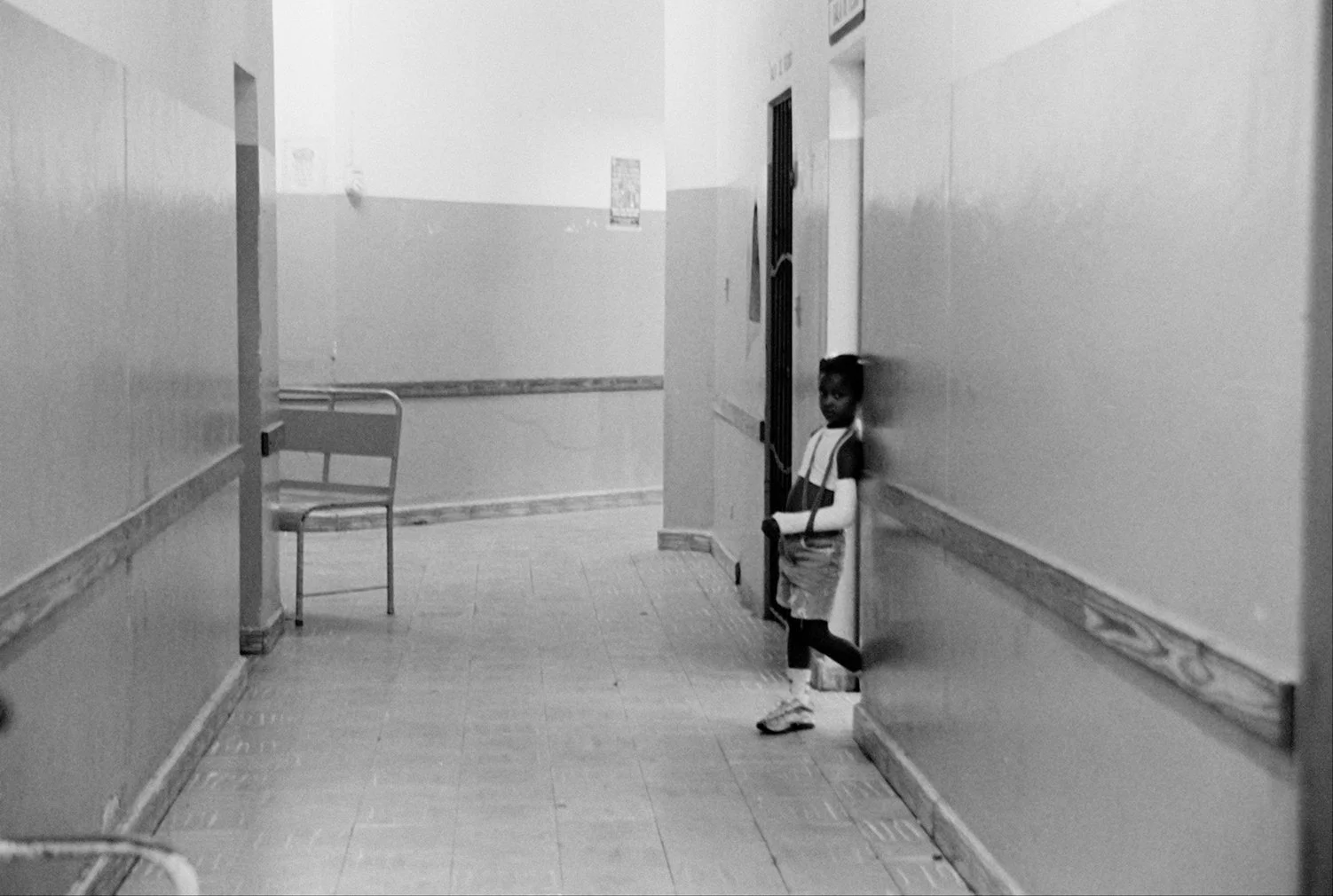

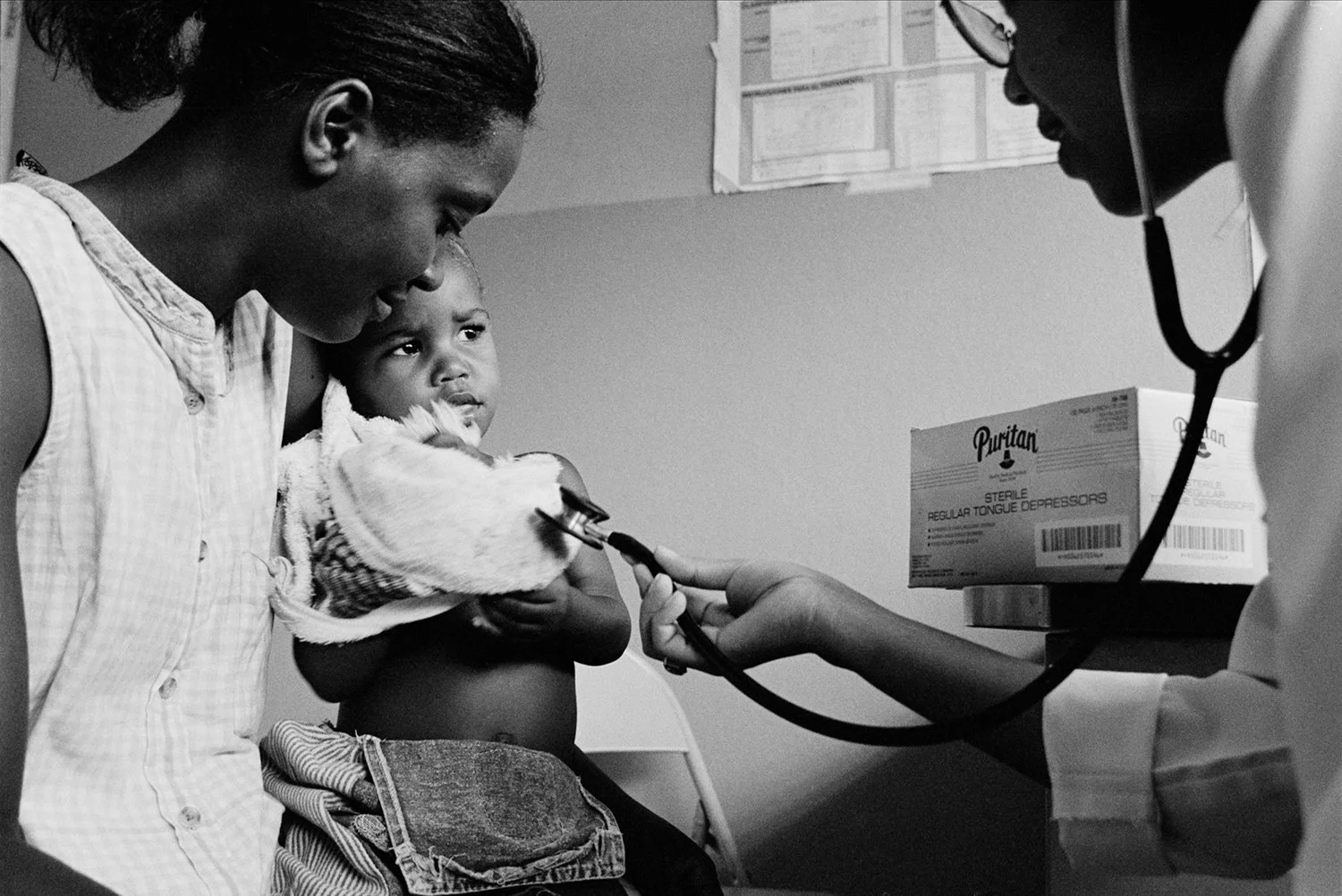

Bani Hospital

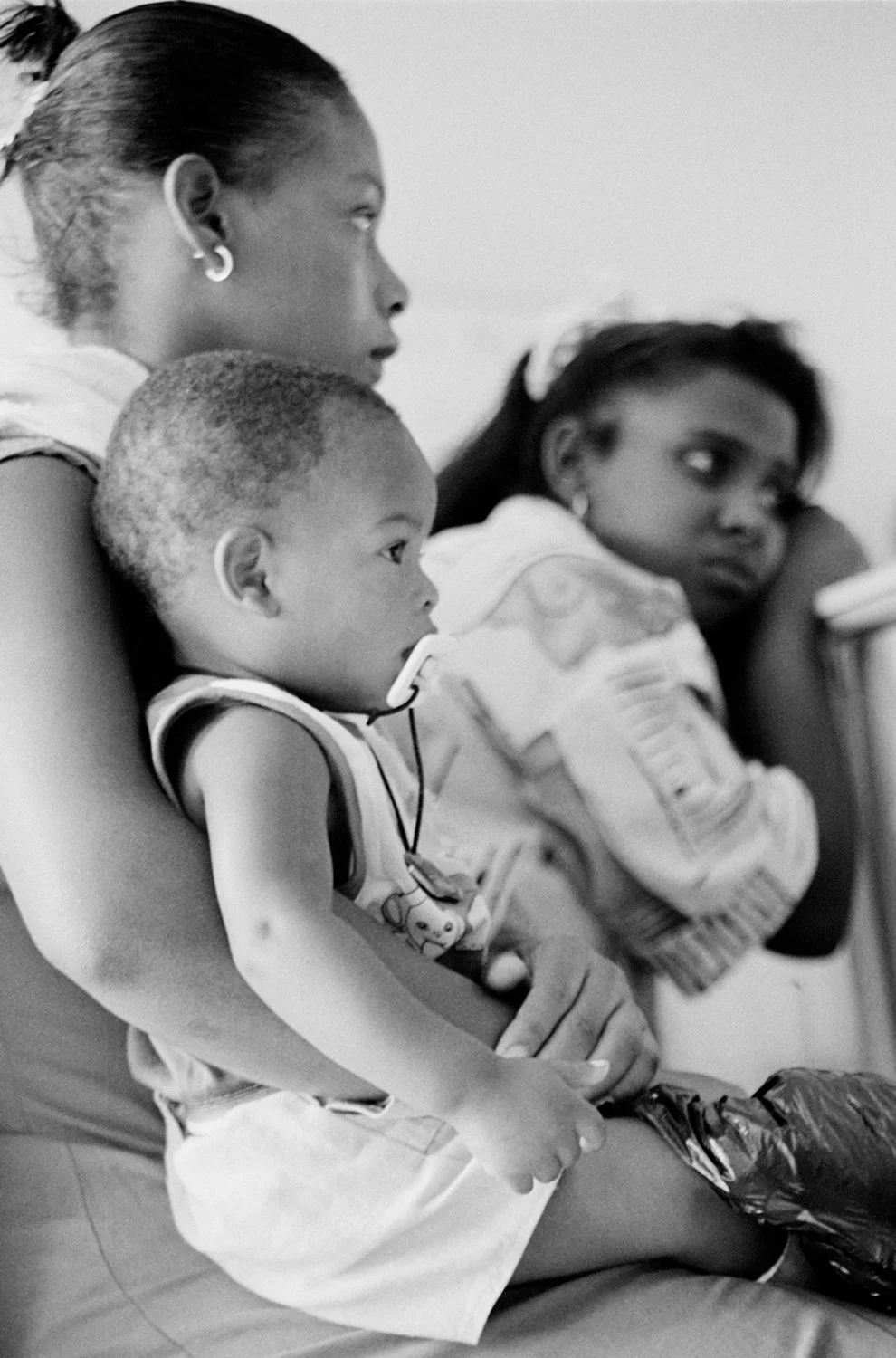

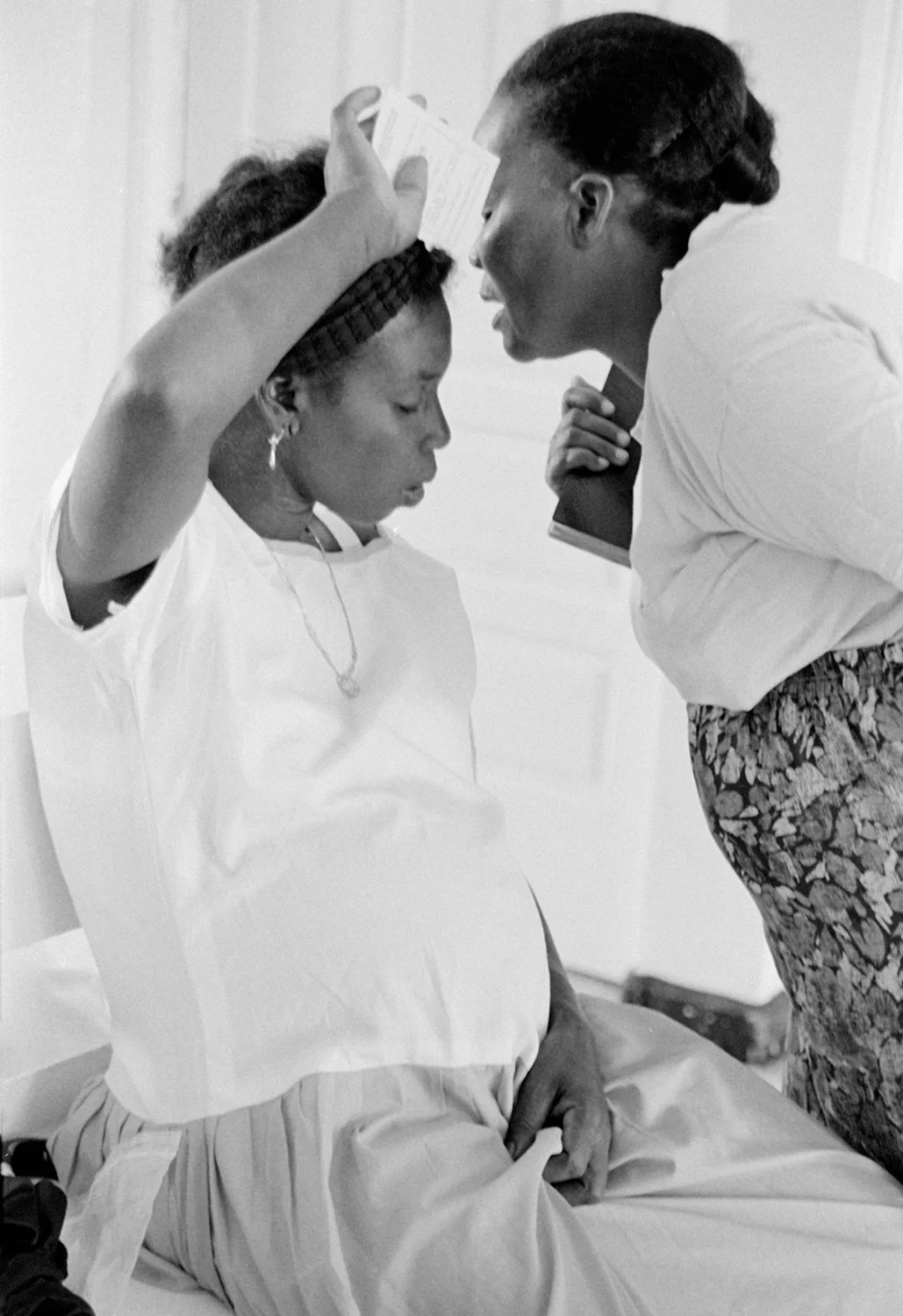

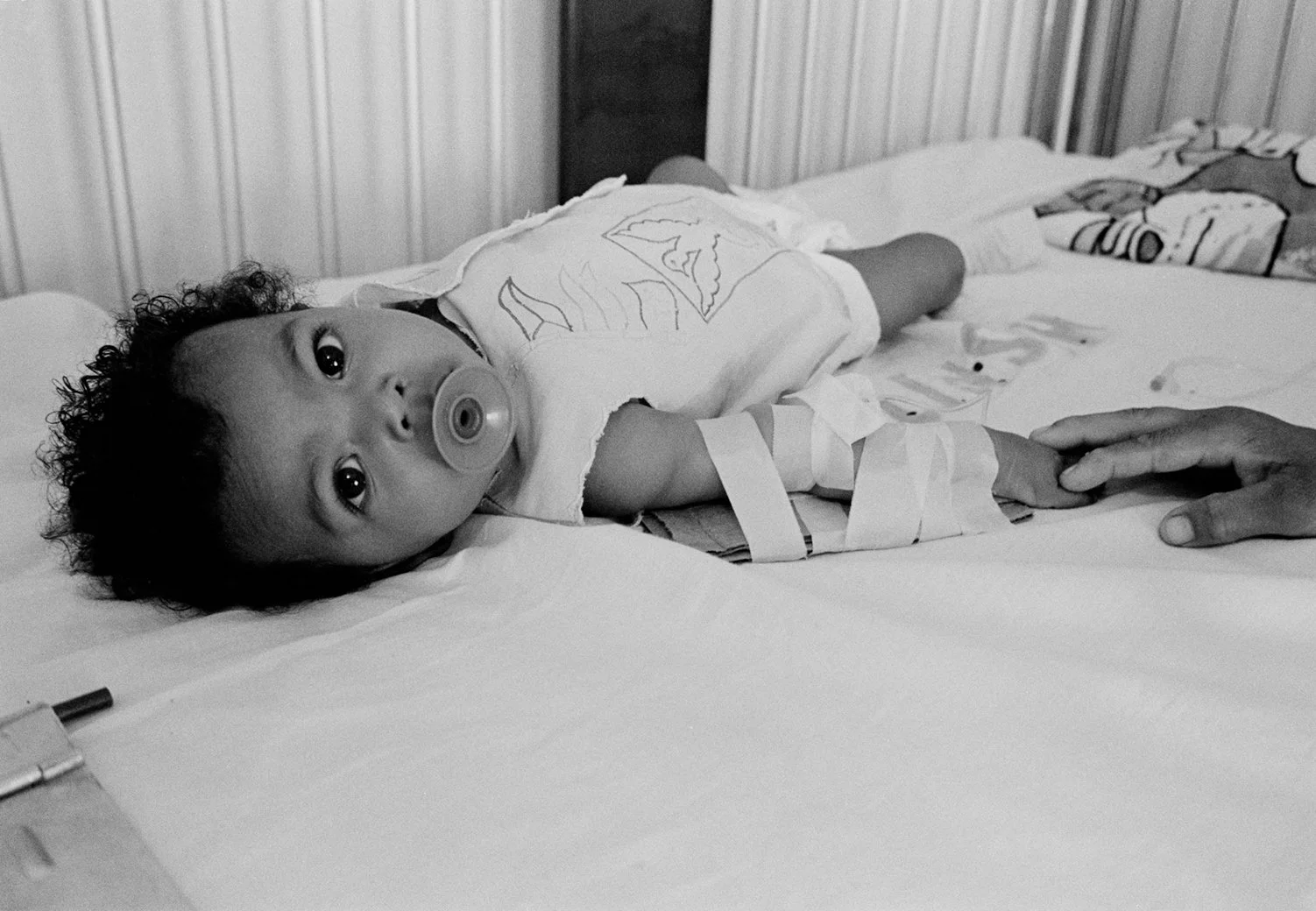

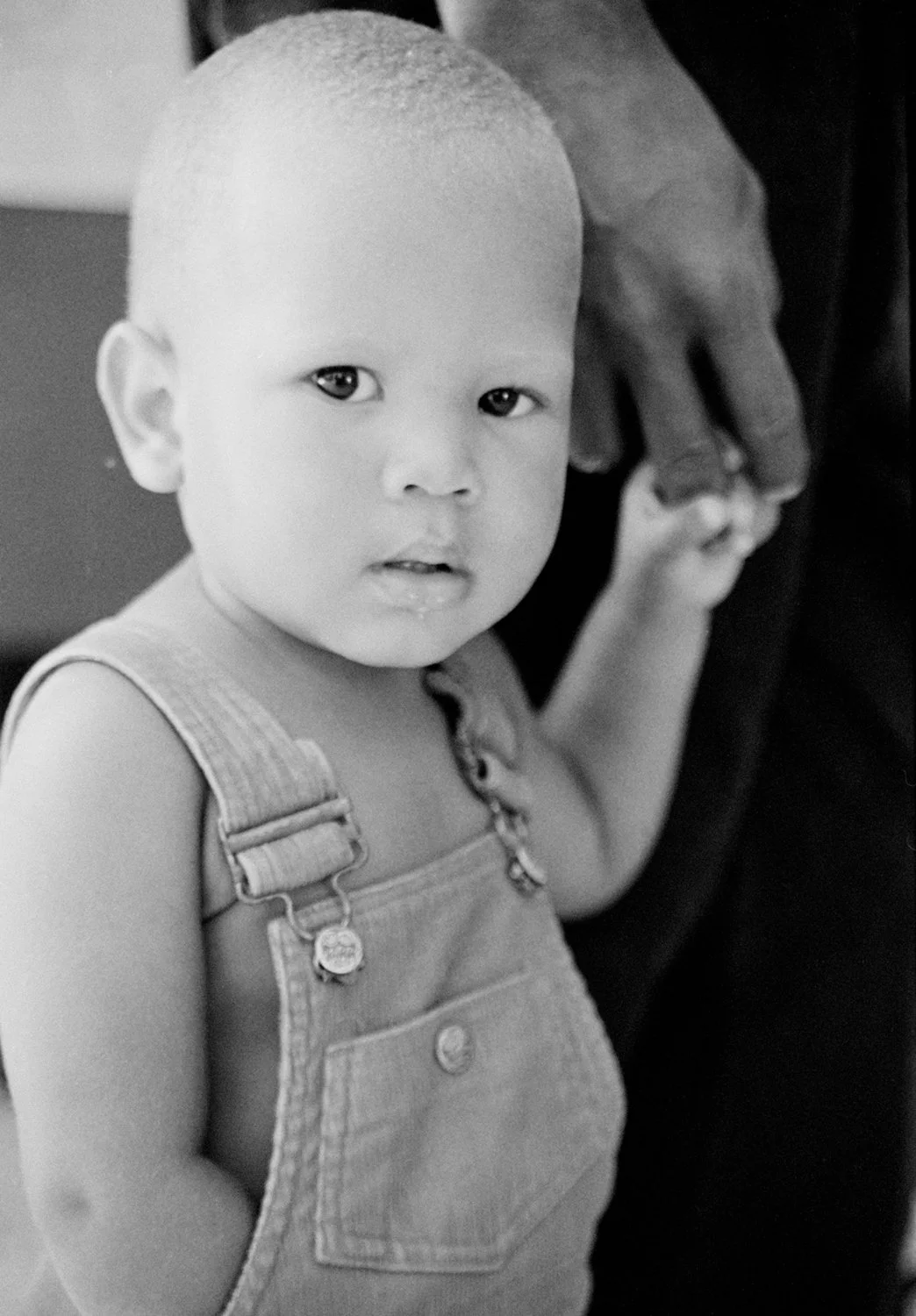

May 15, 1999. I was mistakenly taken to the big hospital in Bani instead of the clinic in Bayaguana, and compared to the relative calm of the clinic, the Bani hospital felt like entering hell. With gates and bars on the doors, it looked and felt more like a prison than a hospital, and within the first 15 minutes I was overwhelmed. I went up to the maternity ward because I thought it would be easier to handle, but I walked into a room full of beds filled with mothers and their babies, and the smell of urine and feces was overwhelming. Women were laying there, half dressed and lifeless, sprawled on their beds. Some paid attention to their babies, some didn't. I started to lose it. I wandered around and tried to find a place that I could connect with, but everything felt so assaulting. I saw women who looked like they had their life sucked right out of them, or were bleeding or in pain, and I asked myself, "How can I photograph them like this?". A camera does not belong in there. I know it is important for other people to see what I saw in the hopes that they are moved to action to help, but I can't take these pictures. They are people who in their most vulnerable moments deserve privacy and dignity. I felt that I had no business being there, imposing myself onto these people's lives.

Life & Death

I have spent a lot of time over the years thinking about, reading about and witnessing death in its various forms, and how death affects life and the living. But what I have seen in these hospitals is not death. But it is not life, either. It is that place of profound suffering in-between.

Giving Back

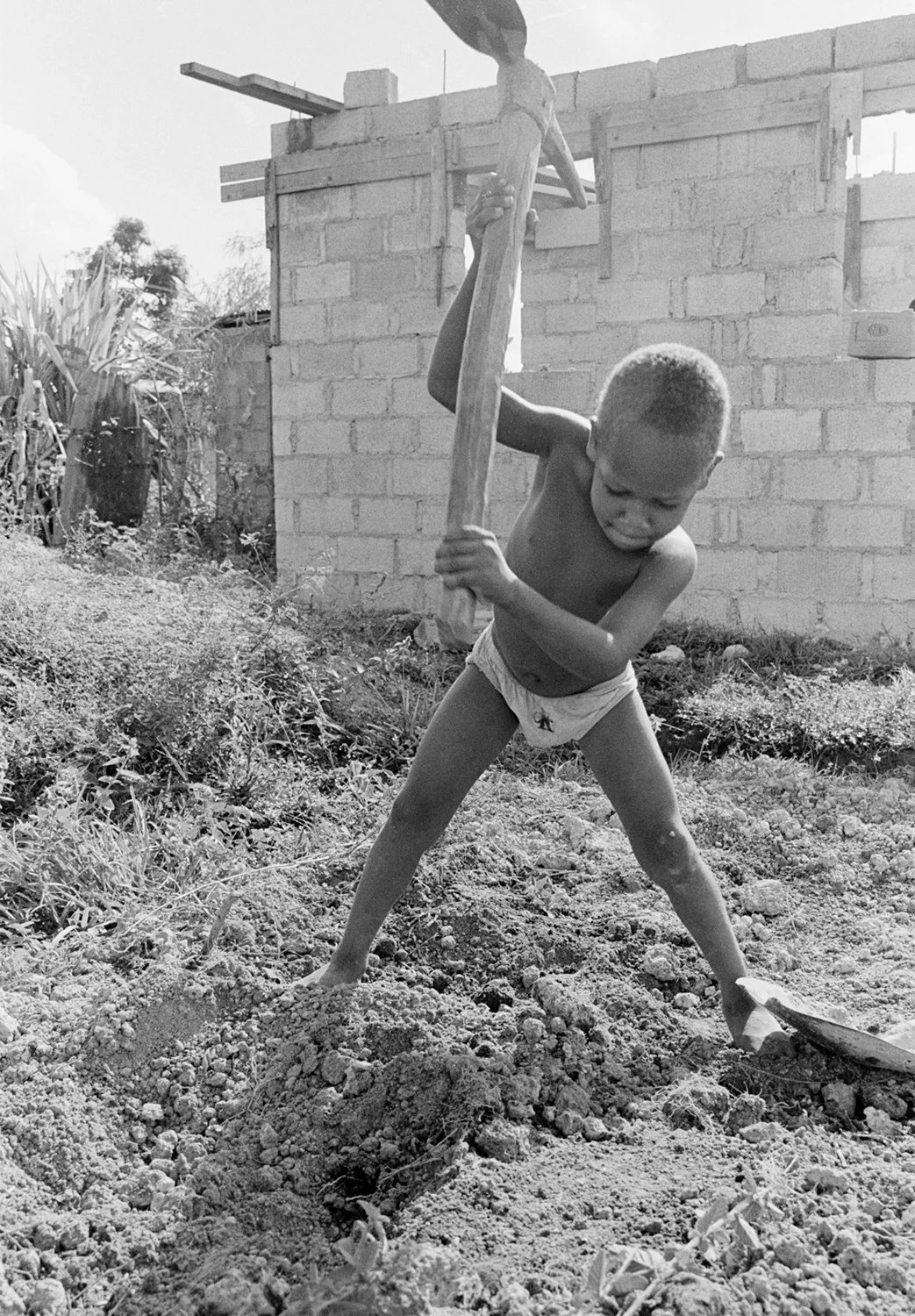

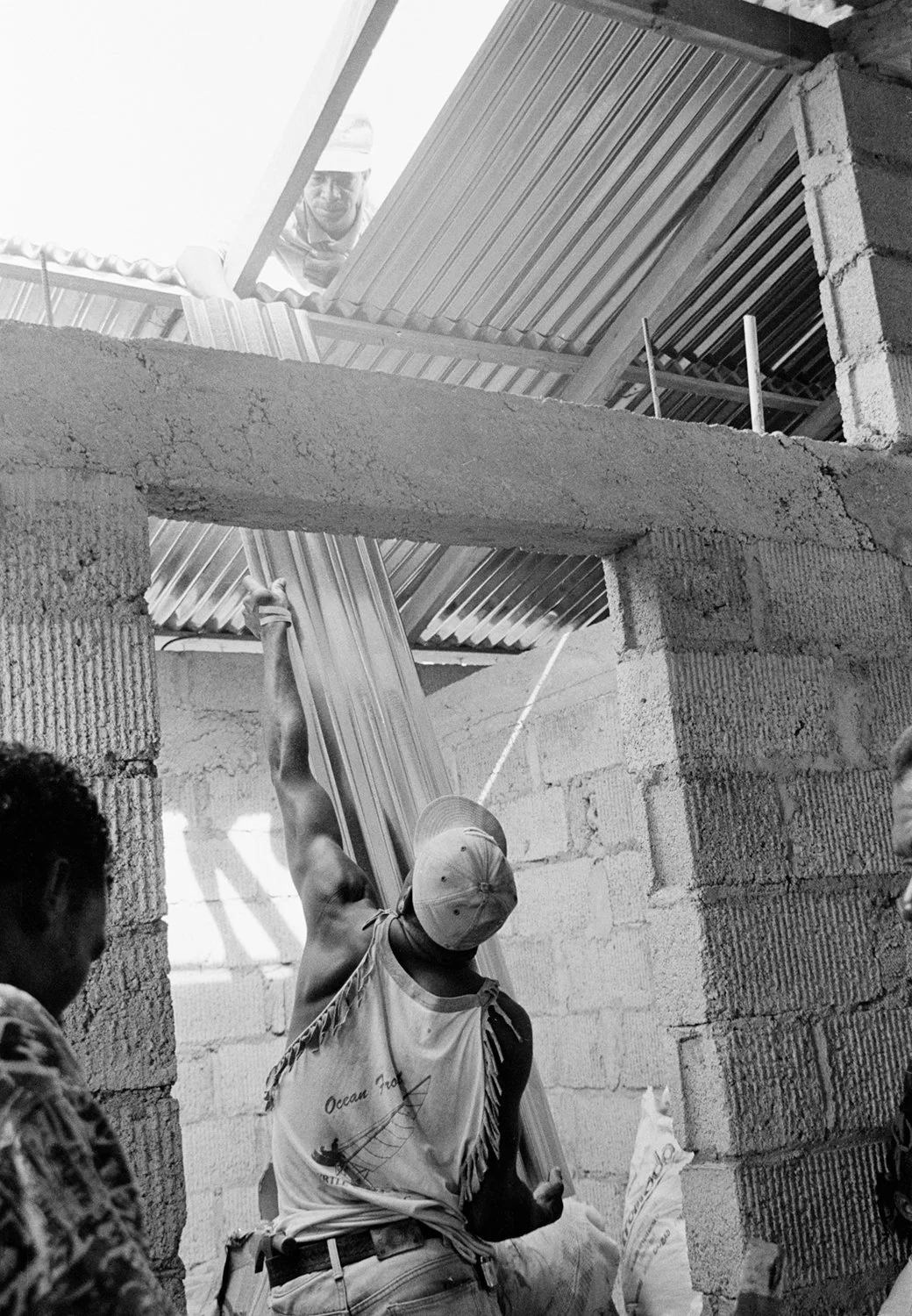

We had raised a bunch of money for this project, and as the work progressed, we realized we would have some funds leftover and we discussed what we should do with it. One suggestion was to help one of the women who had been helping us. She was a 24-year-old single mother whose house had been destroyed in Hurricane George, and despite her own personal struggles, she donates her time working in one of the hospitals where we had been photographing. She used to sell fruit out of the front of her house to make money, but she was forced to stop, and when we met her she was living in a house that she could be kicked out of at any moment. We offered to help rebuild her house with our remaining funds and volunteer labor.

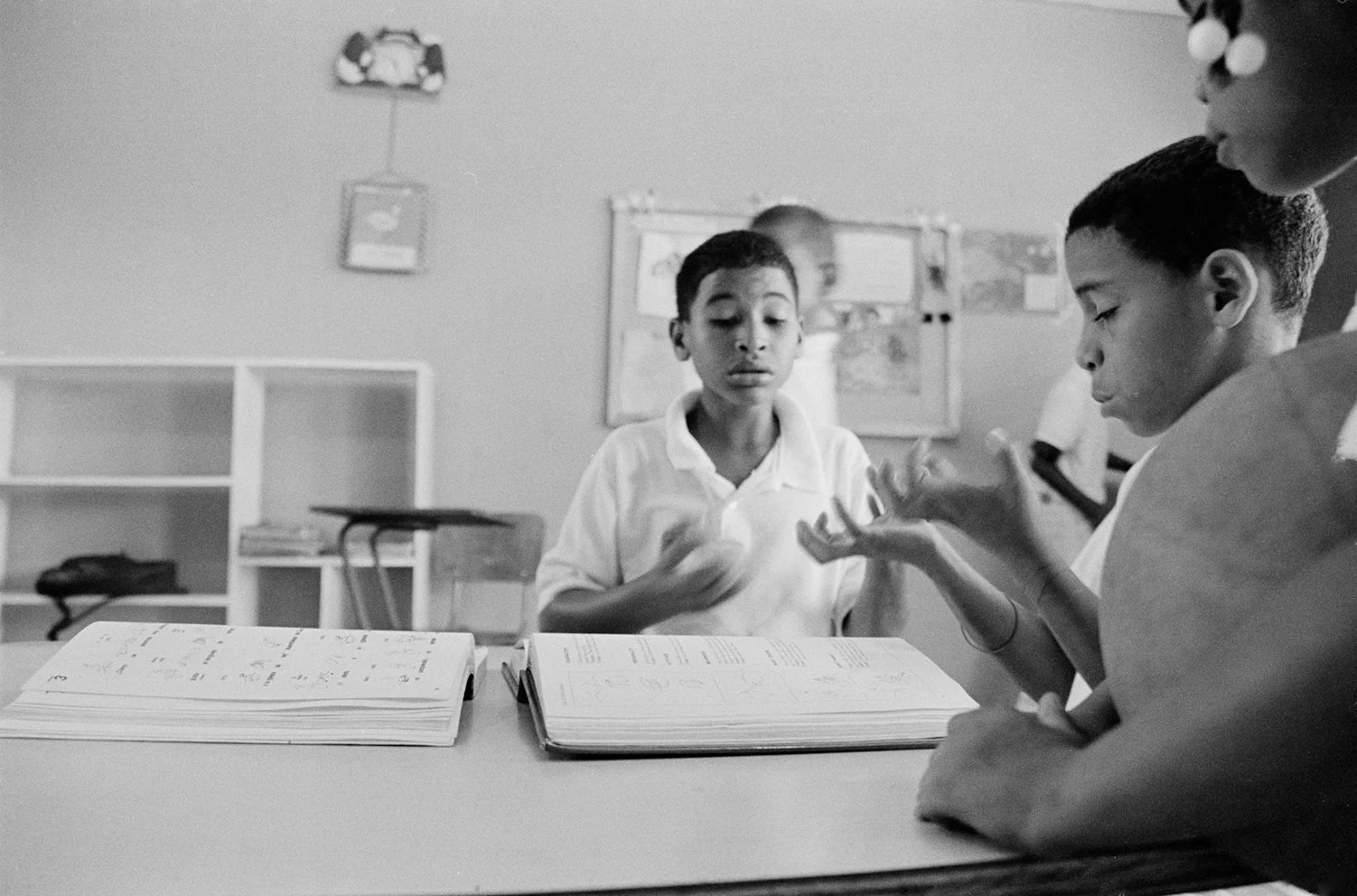

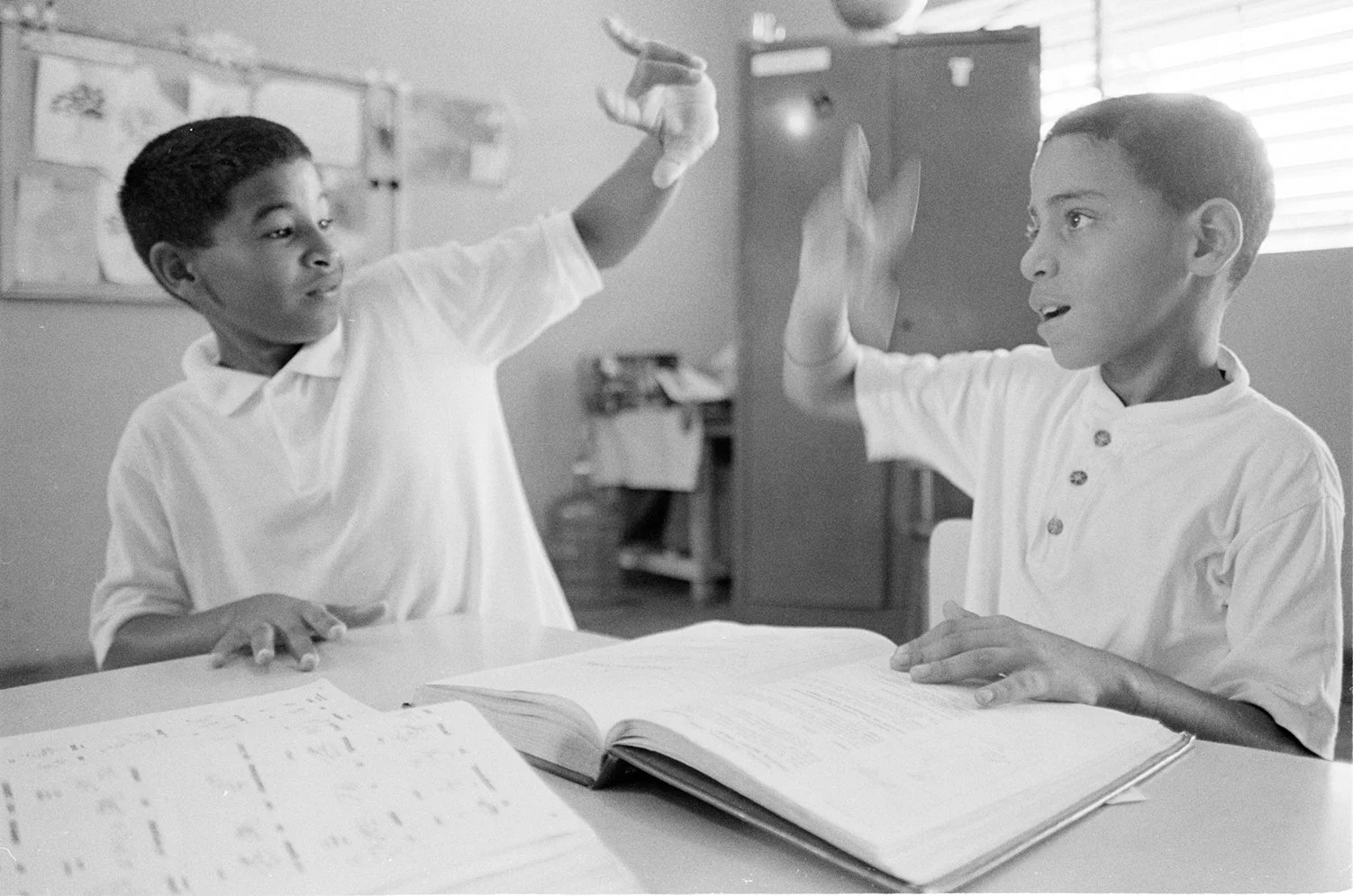

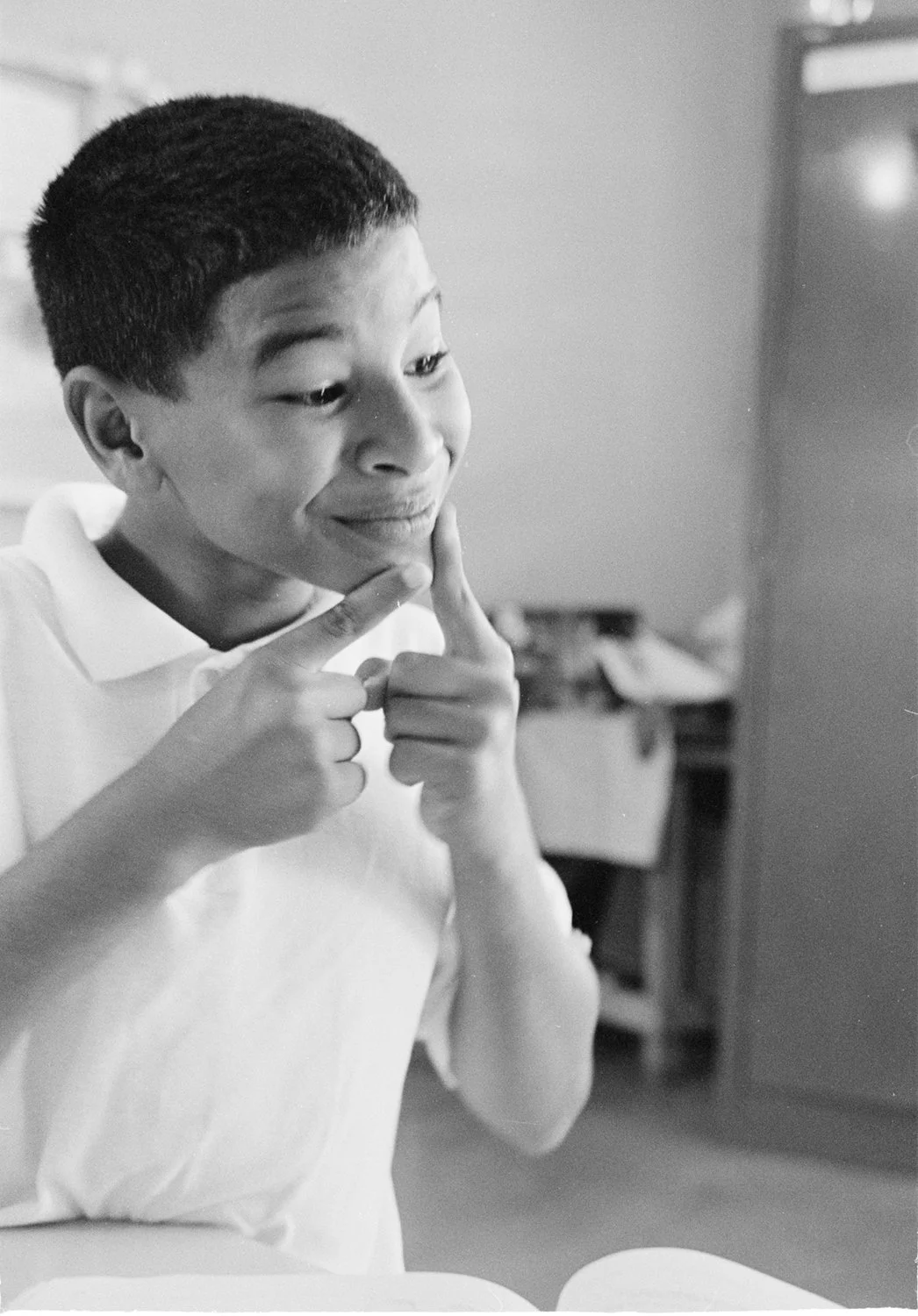

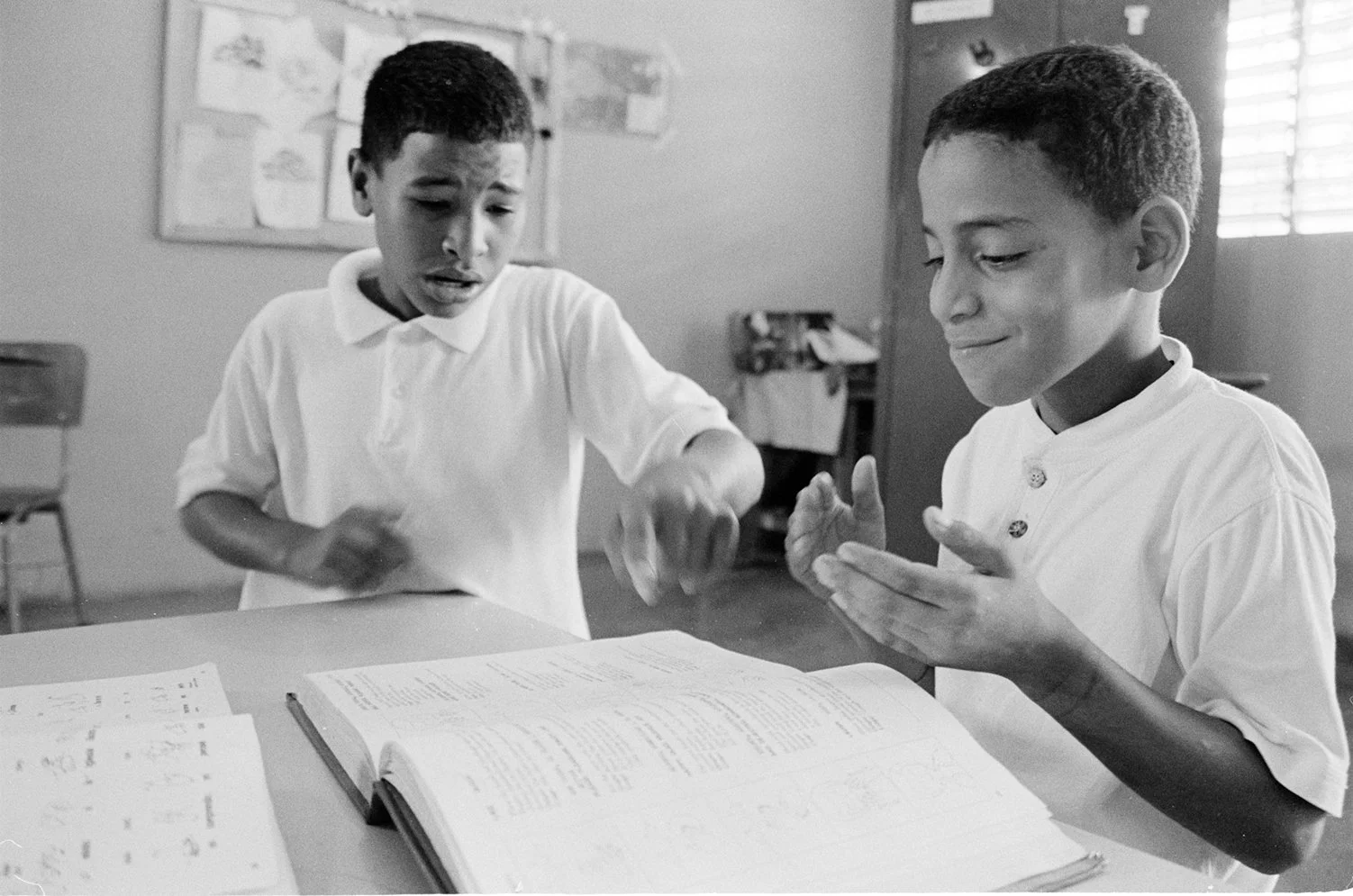

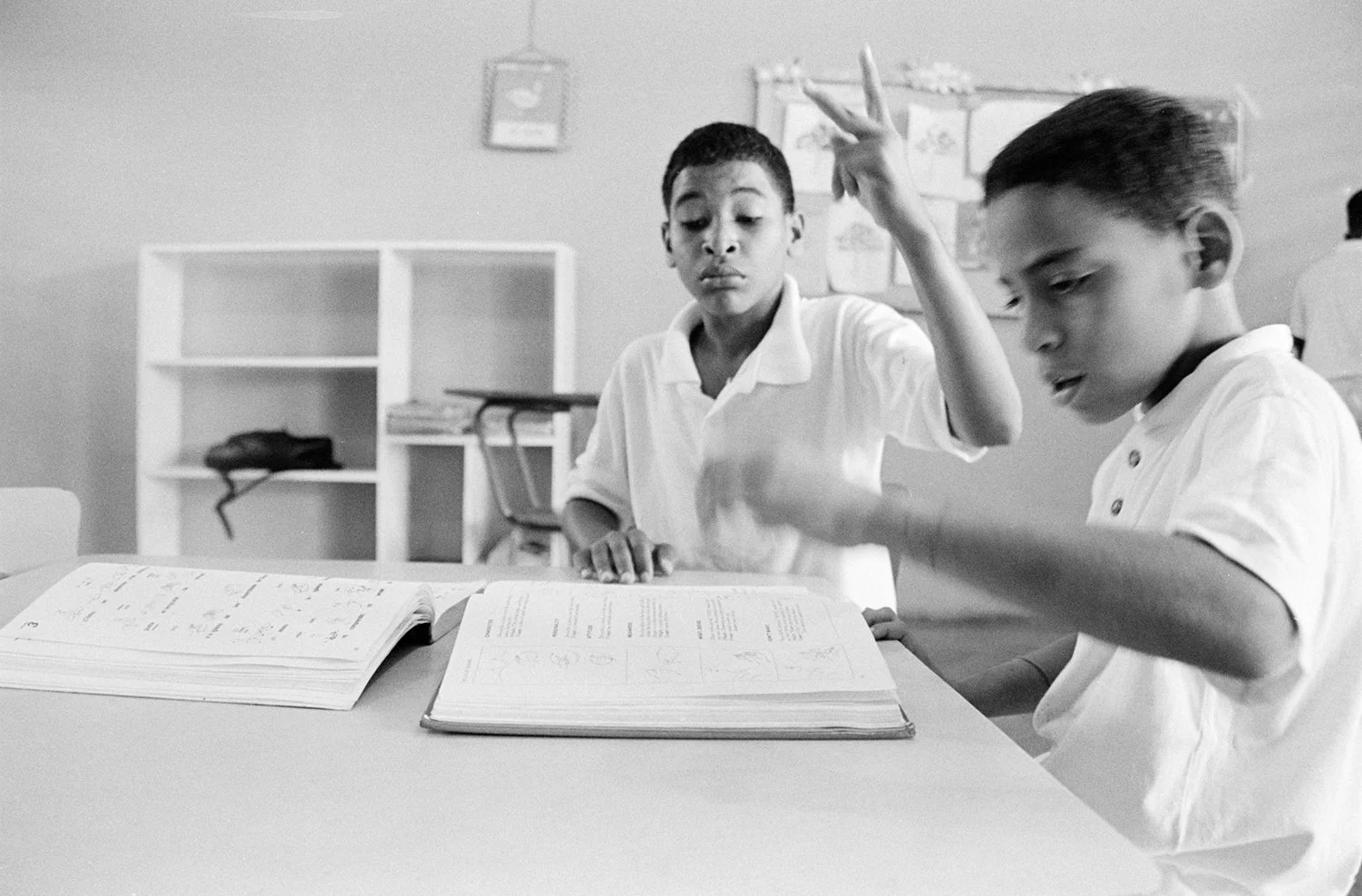

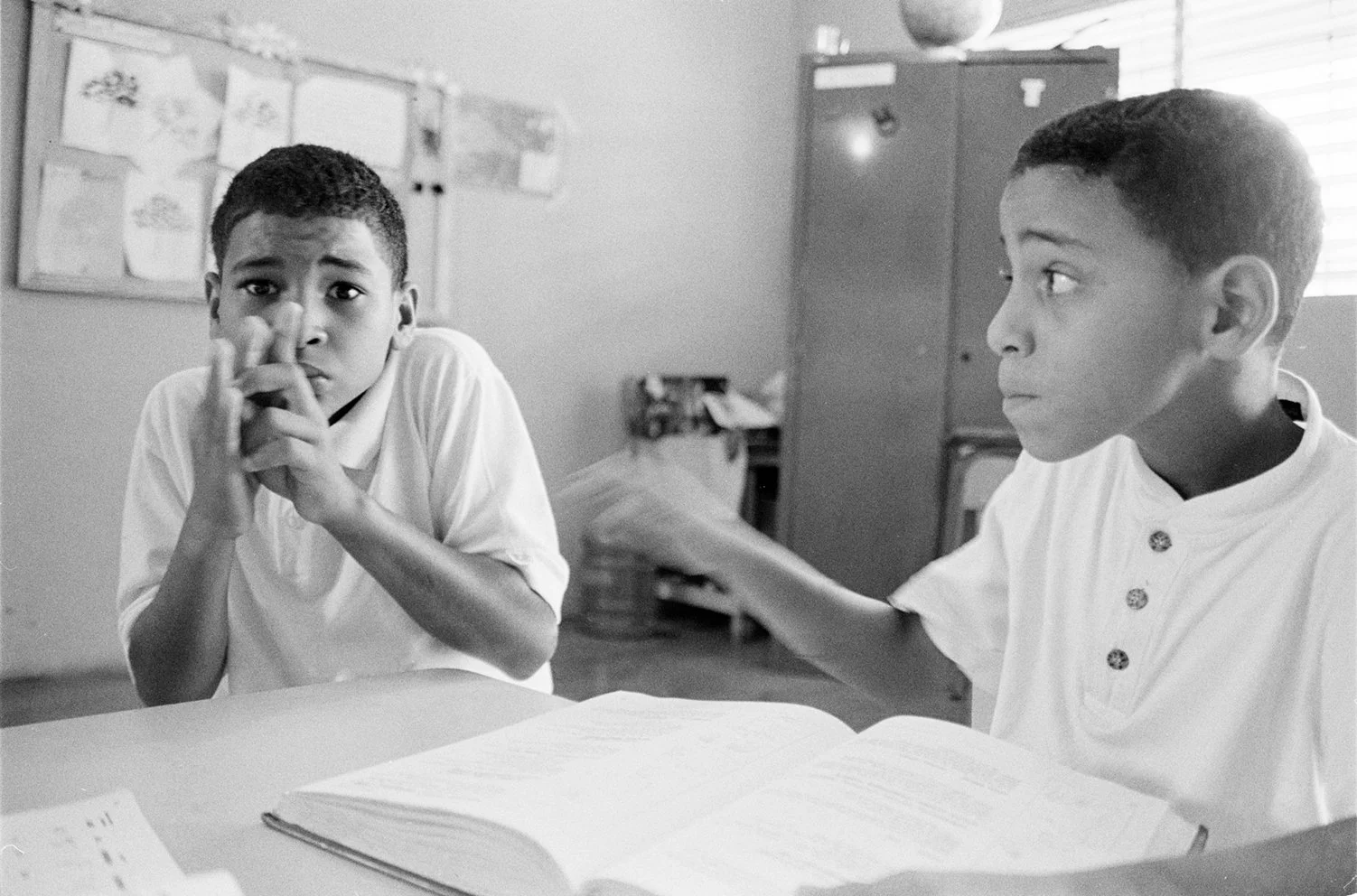

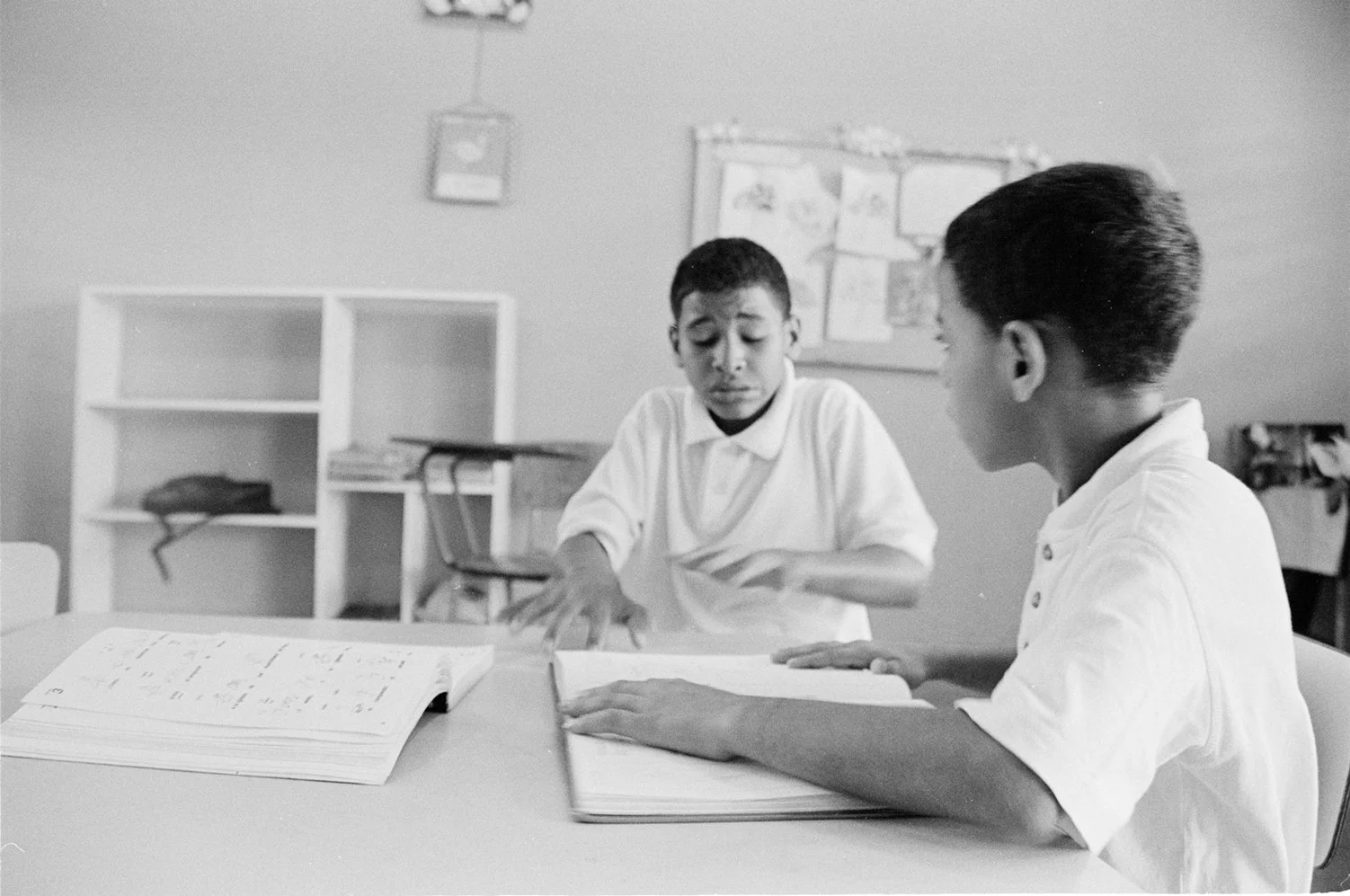

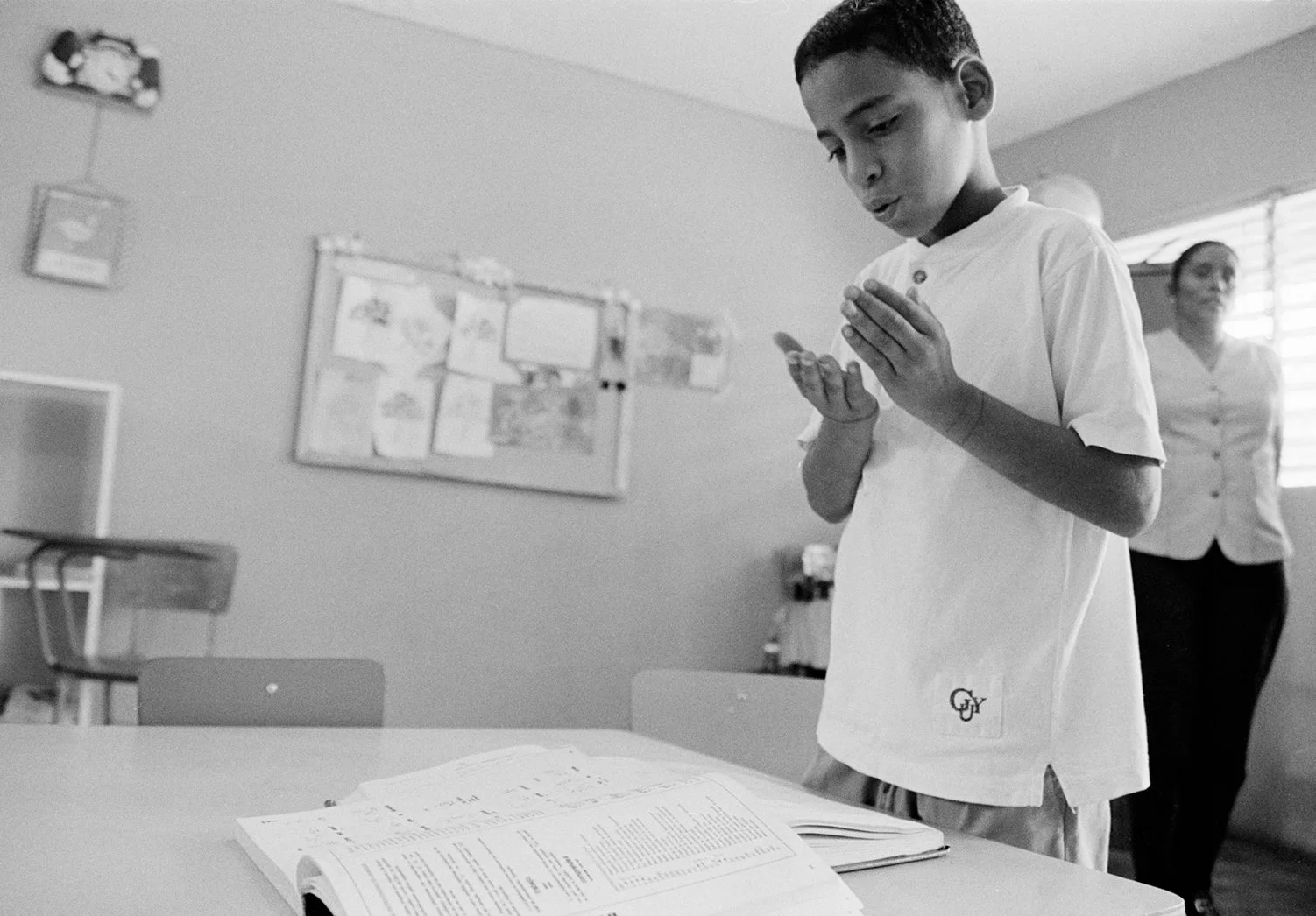

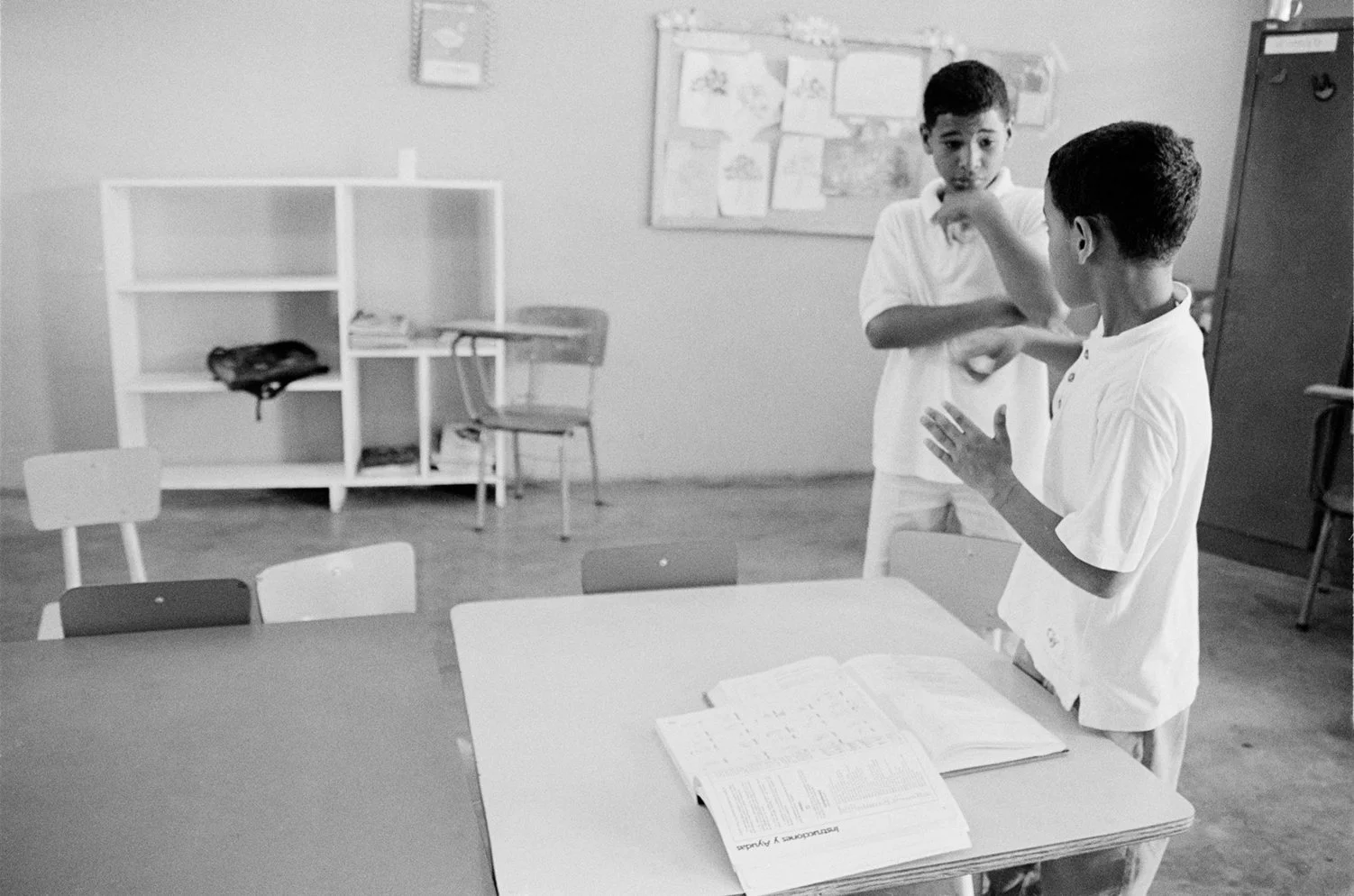

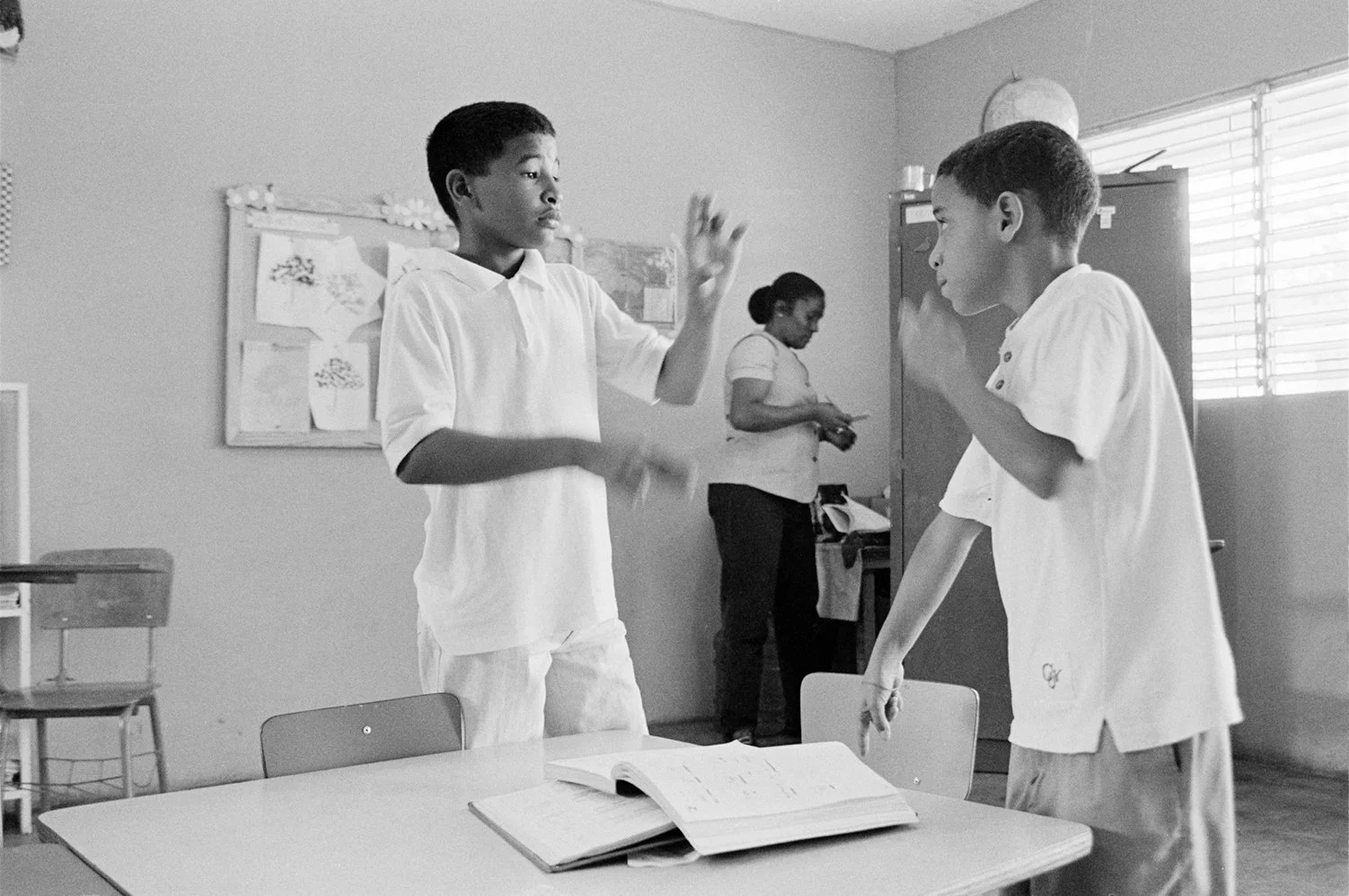

School for the Deaf

We took a day off from the project and traveled to Puerto Plata, where the team split up to explore on our own. One of the other photographers and I stumbled upon a school for the deaf, a private school. The teacher allowed us to come in and photograph her classroom, and we had the privilege of witnessing some very enthusiastic students studying sign language. We also witnessed the same disparities of access caused by wealth inequality that we see in the US, even in this relatively poor country. While the boys in the classroom got the benefit of being able to attend this private school, giving them hope of not being so limited by their disability, another boy whose family could not afford the tuition sat on his bike in the doorway of classroom, trying to learn as much as he could from a distance.